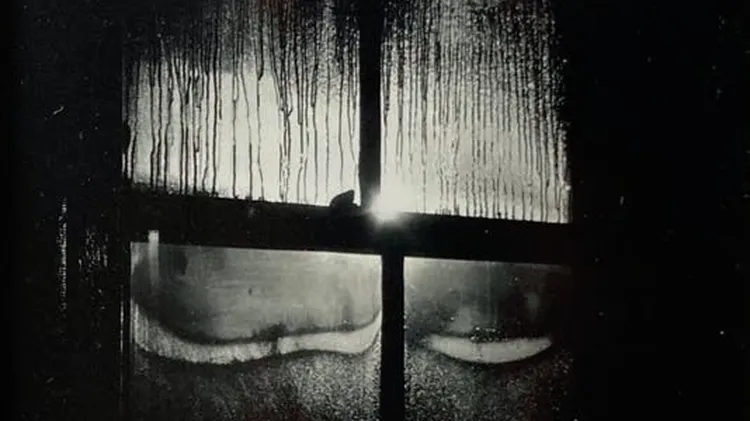

Always marrying the personal with the political, PHILIP GUSTON

Philip guston: passion painting

4 min read

This article is from...

Read this article and 8000+ more magazines and newspapers on Readly