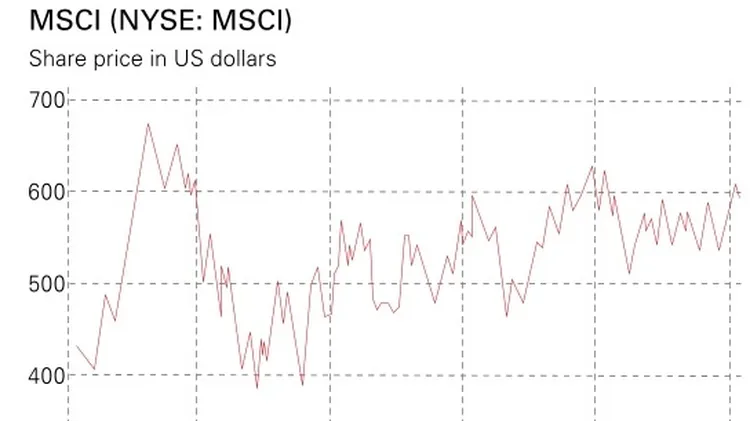

Small stocks may beat larger ones in the long run, but the results

The unreliable size effect

2 min read

This article is from...

Read this article and 8000+ more magazines and newspapers on Readly