The West’s punishment of Russia for invading Ukraine has not had

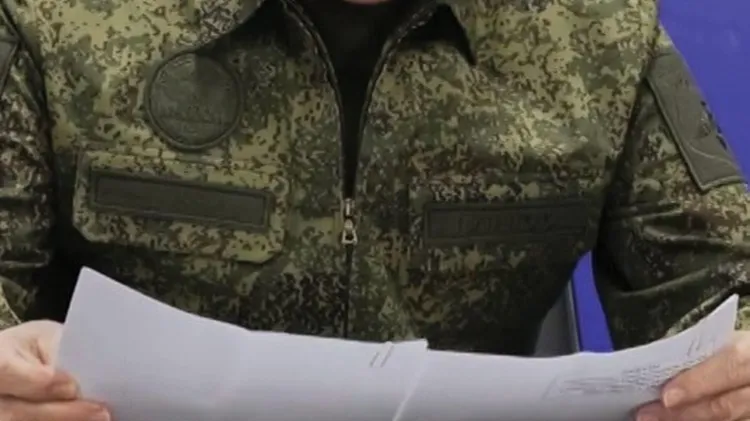

Russia shrugs off sanctions

3 min read

This article is from...

Read this article and 8000+ more magazines and newspapers on Readly