In the years af

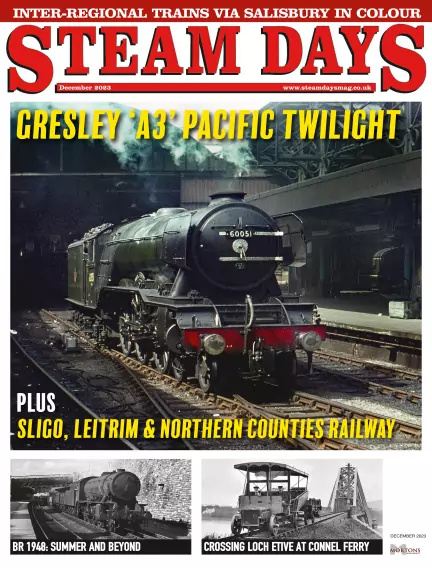

The sligo, leitrim & northern counties railway cattle to the markets, and more

15 min read

This article is from...

Read this article and 8000+ more magazines and newspapers on Readly