After losing her newborn daughter, Hilary Freeman w

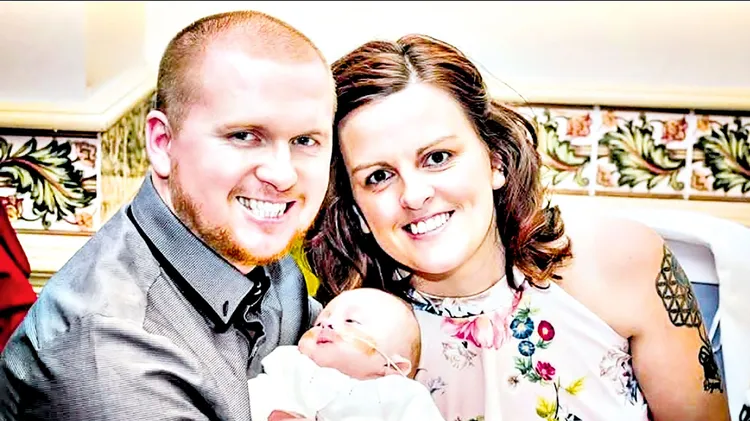

My baby was treated like she never existed

5 min read

This article is from...

Read this article and 8000+ more magazines and newspapers on Readly