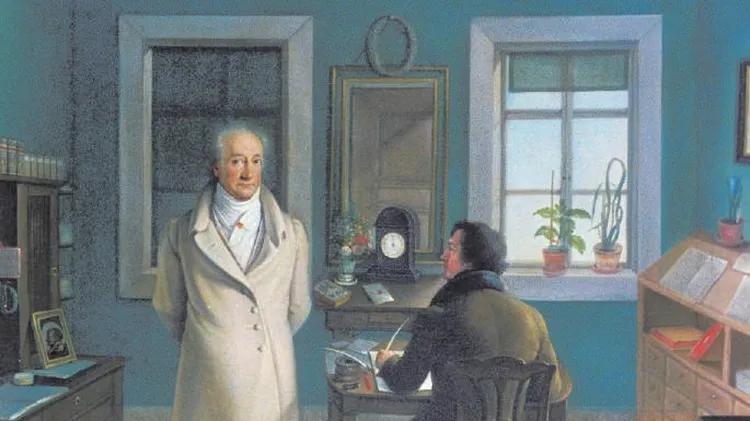

Johann Nepomuk Maelzel invented weird and wonderful devices, but none were more s

Marking time

6 min read

This article is from...

Read this article and 8000+ more magazines and newspapers on Readly